from: „Cornelius Kolig Tactiles“, 1977, © Allerheiligenpresse

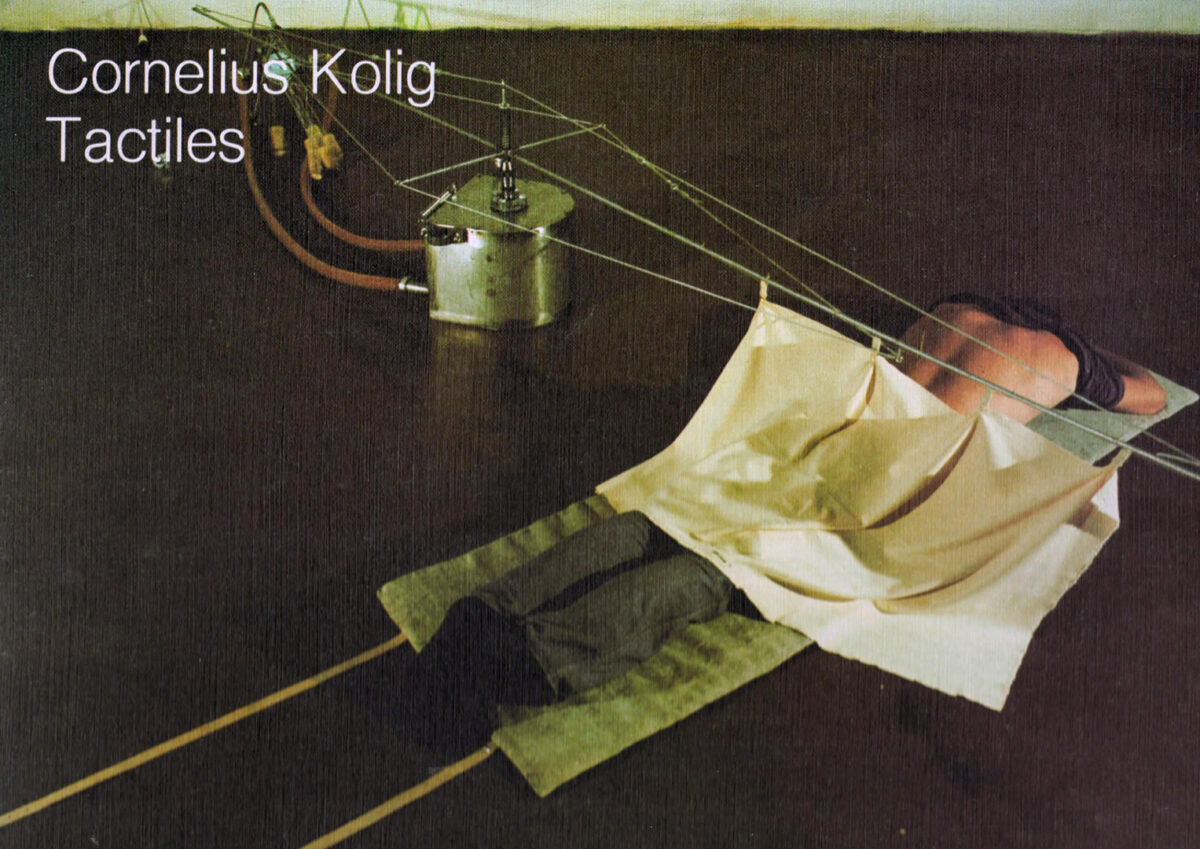

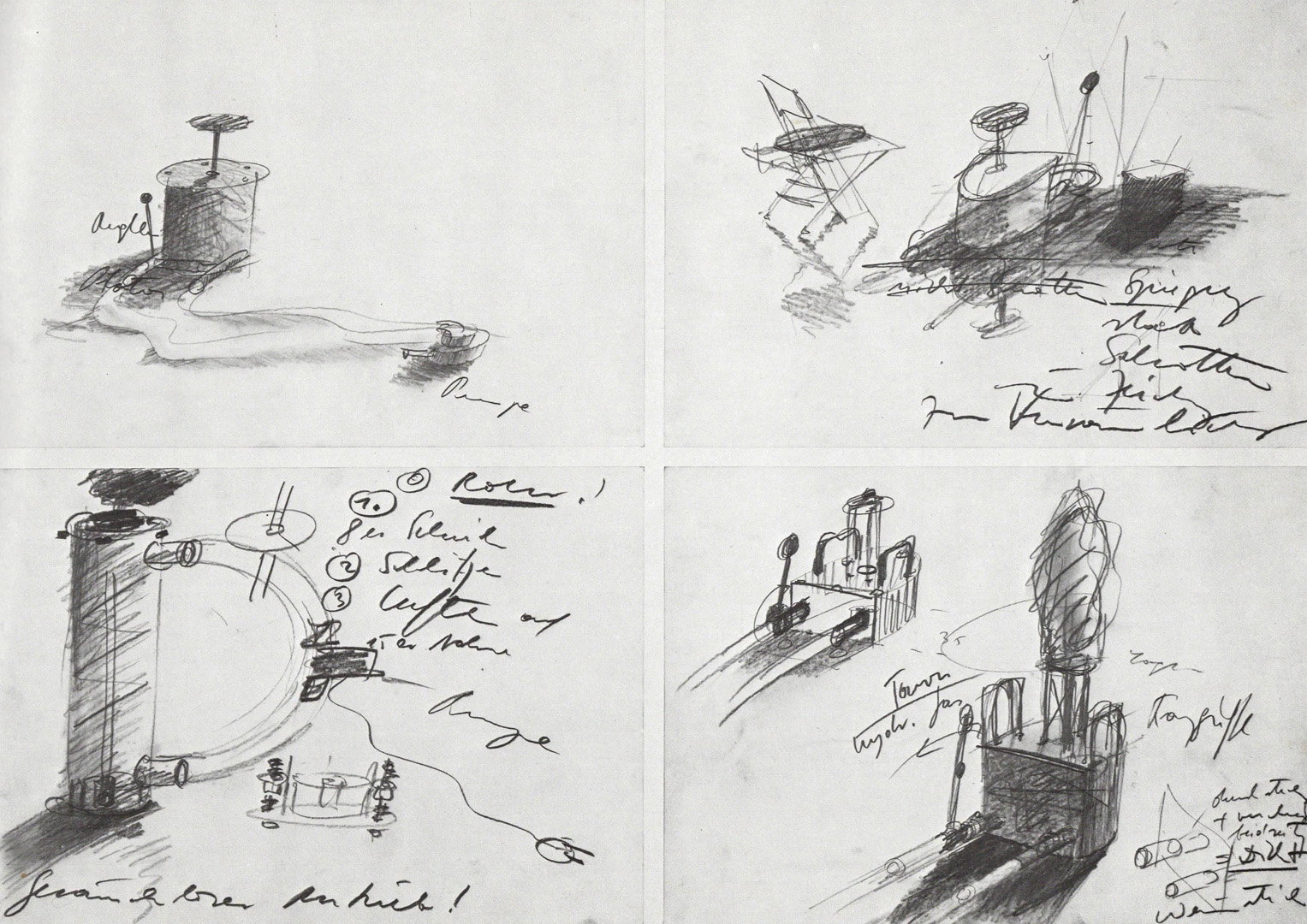

Cornelius Kolig calls his latest objects “Tactiles”, which to a much greater extent than his earlier, organic-technoid “plastic works combining rational coolness and perfection with a romantic overflow” (Sotriffer) have an instrumental character, can be moved and used, but at the same time also “engage the viewer” and thus become fully functional apparatuses. Kolig calls them “stimulus dispensers” in order to emphasize their much stronger tactile quality.

The earlier objects, which played with all the aesthetic stimuli of the new plastic materials, already manipulated the viewer, stimulated him and activated psychomotor reactions, provoking him to act. His work at that time must be seen in connection with the works of the Coop-Himmelblau, which constructed apparatuses for psycho-physical relaxation, or with the proposals of the “Hausrucker” group, who were concerned with a utopian concept of art that played with new forms of life and behavior using the latest technology and that placed art and life in one. These 7 new works by Kolig also confirm a tendency for art and non-art to become much more interchangeable, for the artist to use his means to gloss over and analyze contemporary phenomena… … the artist defines art less through any intrinsic value of the art object than by furnishing new concepts of life style. (J. Mc, Hale)”.

The artist’s engagement with the world of the machine is old, while the idea of the artist as engineer and behavioral scientist is more recent. Since La Mettrié’s “L’ Homme machine” (1747/48) at the latest, the human organism and the machine have been identified. Living in the machine age, consciously or unconsciously influenced by it, artists have dealt with the machine critically and ironically, but also affirmatively. For artists like Tinguely or Calder, but also among the younger ones like Panamarenko, the machine is an instrument that allows them to be poetic. Art & Technology programs have tried to take away the artists’ fear of using technology for artistic purposes. In Kolig’s work, the most diverse moments come into play. His machines are also objects made from a wide variety of materials, whose aesthetic character is expressed precisely through the form of the installation.

On the one hand, the artist is a utopian delight with his stimulus dispensers, but this must be qualified at second glance, as this happiness has the dark background of a Huxleyian “New Brave World”: with his instruments he wants to add new physical stimuli to those already present, at best also copy stimuli, transfer them from man to machine, and on the other hand, behind the non-binding character of the game is the possible idea of a terroristic repetition ad infinitum. If at first glance these instruments appear to be the “good machines” that could replace or extend human capabilities, they also presume to have capabilities that only exist in the interpersonal sphere. The stimuli that they convey with their complicated technical instruments, their interchangeable inserts in their installation between gym, operating theatre and torture rack, do not initially betray the ambiguous character of the game and the presumption of generating precise and standardized sensations. The machine becomes a mechanical counterpart, a partner that provides a catalog of tactile stimuli without reacting to the counterpart.

The machine becomes an automaton that distributes stimuli in a pre-programmed and calculated manner. It is precisely this preparation of stimuli in their manic and exaggerated form that connects him, as well as the ingenious technique, with Ungerer’s “Sexmaniac”, even if the hedonistic aspect does not yet spill over into caricature. Moments of alienation and eternal repetition, of artificiality and isolation, a world of exploited stimuli become visible. Physicality, erotic physicality is only understood in its pragmatic dimension.

What Richard Hunt notes of Francis Picabia’s drawings also applies to Kolig… to compare man’s most subtle feelings and his most passionate, noble, yet murderous ardor to the movements of a machine is to indulge a very naughty sarcasm and a great deal of auto-irony.” The lovers become feasible, “… designed like plastic on blueprints and built into oxygen devices and drying hoods”… Walter Killy remarked on Ungerer’s drawings, the lover shrinks into the complicated mechanism of a Godemiché.

Harald Szeemann was right to include Kolig’s instruments in the context of his exhibition “Junggesellenmaschinen”, where sexual and mechanical vocabulary are seen together, where the machine becomes an erotic counterpart, a projection of cool calculation of the stimuli to be expected.

Kolig stages this mechanics of stimuli when, for example, he brings two breasts made of latex onto two softly swinging podiums by pumping milk in and out to create alternating manifestations of flaccidity and fullness and invites the viewer to touch them. He and some of his “bienfaiteurs” are certainly amused by the macabre industry that offers mechanical surrogates for the human partner. However, by paraphrasing their products and transferring them to a different frame of reference, he reduces them to their real-affine and abstract-analytical core content.

A surreal moment lies in the projection of the erotic and the technical, to which the Surrealists and Duchamp already referred.

Kolig’s machines, which unite the critical and the playful and hedonistic in equal measure, are technically manufactured with extraordinary precision. The sculptural effect, the interaction of the materials has been observed with great care and documents Kolig’s fascination with the “perfect, industrially manufactured” machine.

“Tactiles” are stimulus dispensers that offer the most diverse forms of touching, grasping and comprehending, pressure, smell, temperature, humidity and stimulation current, as if in a utopian science-fiction massage parlor.

The machines release the viewer from his passive role as spectator and invite him to use his hands. They simulate stimuli and remind us of stimuli, they prepare and convey individual experiences in a civilized world flooded with stimuli, in which individual stimuli are quickly consumed and hardly experienced.

Peter Weiermair

This book was produced in an edition of 2000 copies. It was published on the occasion of the exhibition “Cornelius Kolig, Tactiles” in the Kunstvereinfür Kärnten, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt (1977), in the Galerie im Taxis Palais, Innsbruck (1977), in the Palais Thurn u. Taxis, Bregenz (1978) and in the Gesellschaft bildender Künstler Österreichs, Künstlerhaus, Vienna (1978), as well as on the occasion of the presentation by the Galerie Gras, Vienna, at the international art markets of Cologne, Vienna (K 45) and Bologna (1978).

Publisher Allerheiligenpresse, Innsbruck 1977